Everest Base Camp

When we asked our friends to set us challenges to complete on our year abroad, we were expecting some smart-arse responses. Danny Schwarz, however, took the biscuit: “Think of a challenge greater than all the other challenges. Do it.” This got us thinking: what would actually be a sustained challenge, something beyond a laugh or an adrenaline rush? We hope, Danny, that you think climbing to Everest Base Camp fits the bill.

And my apologies for writing this up almost a year later, after I’ve just about got my breath back…

Setting off for Everest Base Camp, we were pumped. Jonny and I had spent nearly two months in Bali, eating healthily and attending fitness classes every day, and we were feeling in “peak” condition. Puns aside, we’re no Edmund Hillary and Tenzig Norgay, so we weren’t planning to get to the summit of the world’s tallest mountain; we only wanted to stand at its base and ogle at the feat of those who had. Of course, we knew this was going to be a tough couple of weeks, but we were ready and, after the easy day-to-day life of Canggu, we were itching for a challenge.

First stop: Kathmandu. This bustling city is a must-do on any trip up the mountain. Sure, it’s not particularly pretty, and nor is it high above sea level so it doesn’t help with acclimatisation. However, it’s where you buy the first of the two permits required to climb Everest and it also provided us with all the gear we needed for the hike. After all, we had been travelling in sunny climes for our adventures abroad and didn’t feel our shorts and flip-flops would cut the mustard on day-long hikes in sub-freezing temperatures. An entire section of the city, named Thamel, overflowed with shop-keepers and stall-owners all eager to sell trekking gear. If you can think of a trekking brand, there is a decent fake in Kathmandu. Everywhere we looked were various ‘North Face’ or ‘Marmot’ coats, trousers and shoes, being sold at a tiny fraction of the original cost. Certainly, some fakes are better than others but, in the two days we spent accruing our gear, we got pretty good at working out if the garment in question was decent quality or if it would fall to pieces somewhere up the mountain, leaving us frostbitten and wishing we’d paid a few quid more for the gloves with five fingers.

Here’s Jonny trying a sleeping bag out for size, as if the temperature in a Kathmandu shop would be anything to go by…

For better or for worse, Jonny had read up about the availability of porters who help you carry your gear on the trek. We weighed up this option and decided to hire someone to help us, for the following reasons:

- Yes, this is Year of the Challenge, but we figured that completing the hike was enough of a challenge already. After all, we were doing this trek because we wanted to stand at the foot of Everest, not to earn a Duke of Edinburgh award.

- Our travel bags are not designed for trekking so we would have to spend out on new ones, which would then have no purpose after Nepal.

- Jonny’s clowning days saw him incur a shoulder injury which hasn’t healed yet.

- It’s encouraged as a way to support locals.

- At 2000NRP/ day (approximately £14) this was not a huge expense.

- We read that it is reasonable to give your porter up to 30kg to carry. This seemed an obscene amount and we had no intention of reaching our quota. However, it did mean we could reserve some of our weight capacity for trekking snacks, as – understandably – the further up the mountain you climb the more expensive everything becomes.

Now that we’ve finished excusing ourselves for being weaklings, let’s move on. The bags recommended for porters are large hold-alls which are sold at most stalls in Kathmandu. After buying one (and then returning it for a larger version when we realised our marshmallows simply wouldn’t fit), we filled it to the brim with our coats, sleeping bags, toiletries, slippers and snacks. I’m not going to lie: it was heavy. At the airport it weighed in at 22kg and we were stunned that anyone could lug 8kg on top of that up a mountain. If this was going to work, we would have to find a beast of a human to carry it.

(In the photo above, you can see our porter carrying our bag along with the rest of his gear, standing next to another Sherpa who looks to be carrying three times as much. It was insane what these men managed to lug up mountains while the rest of us were short for breath).

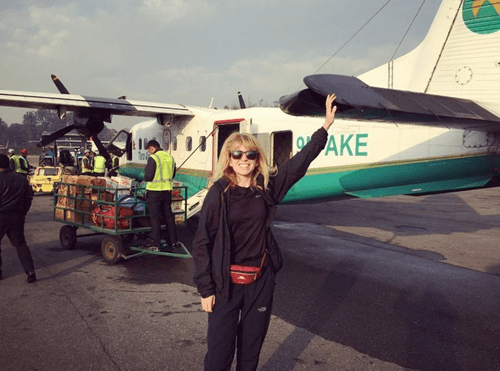

Fully kitted up for our adventure, it was time to board the plane to Lukla. Speak to some Everest puritans and they might tell you that we “cheated”. If you actually want to complete the full trek, you should start in Kathmandu, or at the very least Jiri. It’s a fair point. However, Lukla to Base Camp means that, if you are working within a time-frame, you can complete the best and most challenging part of the hike in eleven days. Standing at 2860 metres above sea-level, this is a perfect town from which to begin the ascent. That’s because most people don’t feel the effects of altitude sickness below 3000 metres, so it gives hikers a couple of days to adjust to the lower oxygen levels before reaching that critical height. Plus, if you need another reason to cut a week off your trek, the plane ride is spectacular.

Yes, Lukla is infamous for being the ‘world’s most dangerous airport’, but chances of having a crash are still incredibly slim and the views you get from the sky are so distracting – snow-topped mountains peek through clouds as you chew on your Air Yeti toffee and stuff cotton wool in your ears – you’ll forget why you were worried in the first place. That’s until you spy the runway from the cockpit and wonder how on Earth a plane whizzing through the sky can land and stop in little over 500 metres. Fair enough, we were hardly flying a Boeing 747, but compare that to that to JFK’s 4.5km runway strip and you have yourself a hair-raising landing.

We had the foresight to book an early morning flight, knowing that many later trips get cancelled due to Everest’s unpredictable weather, which meant that we arrived at Lukla with a full day of hiking ahead of us. Still carrying our heavy bag, as well as the two lighter rucksacks we brought for the daytime, we were eager to find our very own Nepalese Mr T to shoulder our load. Unfortunately, this proved a little harder than anticipated. We had guessed that we would be overwhelmed with choice of porter, having experienced flocks of taxi drivers and service providers competing for our custom in other areas of Nepal, but here there were only a few men eager for the job and they were all under 5 foot 5 and very slight of frame. Later, we were to see men this size and much smaller heaving tons of paraphernalia up the mountain, but we had not yet witnessed the superhuman strength of the Sherpa, so the thought of any of these petite men lugging our monstrous bag 130km was worrying, especially when none claimed to have insurance. Indeed, it is widely recommended that your tour guide/ porter is insured, in case they injure themselves on the mountain. Even the most experienced trekker can develop altitude sickness or slip on ice and paying for a helicopter rescue can be extortionate.

Having promised one another we would wait until an insured porter made himself available, we soon got impatient to begin our hike. A man who had carried the load of two American couples was pointed out to us. He had done a great job, we were told, but one look at him curled over on the sofa, conked out in the middle of the day, implied he needed some rest before embarking on a back-to-back trip. After phoning some tour companies and being told we would only find an insured porter if we were also prepared to take on a guide, we concluded the promise was off. After all, Jonny and I share an unwarranted hatred for guided tours, so a two-week guided hike might just drive us over the edge: un unpromising thought, considering our location. We returned to a man who had introduced himself to us as Deet.

His manner was cool and he appeared slightly hardier than other contenders. His English was beginner level at best, but that seemed relatively unimportant. Something about him (a tenuous physical resemblance perhaps or just an adventurous spirit) reminded us of our friend Dean O’Shea, so we paired that with his insect repellent first name to create the code name ‘O’Spray’. At this point, we couldn’t even blame altitude sickness on our awful sense of humour. However, although we are not usually ones to discuss people behind their backs, this was going to be a long trip to spend with a stranger and felt the name might come in useful. We welcomed Deet O’Spray onto the team. With ease, he hoisted our giant bag onto his back and off we went.

Day 1: Lukla – Monjo (12.5km, 6.5hours) stopping for lunch in Phadking.

Our first hike was a joy. We were below 3000m and fresh, and the scenery – although not yet sublime – was already captivating, with long bridges running high over ice blue rivers and beautifully painted prayer stones at various points. Deet took us to a relatively expensive (and completely empty) restaurant just outside of Phadking. This was to be the first of many times he tried to “guide” us to eat or stay in his choice of location, clearly run by a friend, and we did our best to remain polite yet assertive. After all, we weren’t hiking Everest for the cuisine. Phadking is usually where hikers stop for the night but we were eager to press on. Monjo proved an excellent choice as the lodge we stayed in was the best of the trip, with a log fire and free shower facilities: both of which we would have appreciated far more as we got colder and smellier up the mountain! Moreover, it cut some time off the second day’s hike, which was to prove far more strenuous.

Day 2: Monjo – Namche Bazaar (5km, 4.5 hours)

Although a relatively short hike, Monjo – Namche Bazaar is steep and the further up you climb, the puffier you get. After all, it sees you surpass 3000m. We felt lucky to have Deet by our side, as many other climbers were struggling with the weight of their bags on the ascent. We met a fellow traveller called Mike who, like me, had never completed any hikes of this magnitude, and Jonny shouldered his bag for the last part of the hike. As we turned a bend on the pass, we were guided to look at a gap in the trees. This was to be our first sighting of Everest. Jonny and I were fools of perspective as we believed it didn’t look too far away but we were soon to learn that every hundred metres feels like five hundred the higher up you climb. Passing a man in his seventies or eighties, we heard him bemoan his old age and lack of fitness. “I don’t know if I can do this. I feel like an old man.” Having read that this was one of the more challenging days, we encouraged the gentleman to keep going, assuring him that he was the youngest old man we had ever met for embarking on such an adventure. We hope he managed to rest up in Namche and complete the hike, but we didn’t see him again on our trip. I only hope our words of encouragement didn’t finish him off!

Namche Bazar is a wonderful town, strikingly set on the mountainside with a wealth of hotels, restaurants and bars in which to relax. Alcohol and altitude is a bad combination when you haven’t acclimatised so we steered clear of toasting the end of a hard day’s hiking with a beer, choosing instead to opt for sugary drinks and a carb-rich meal to keep us going. Jonny was to look back on his hot meal of ‘Lover’s Stew’, made from minced yak and beans, with warm nostalgia, and it was the thought of returning to Namche for this culinary delight that kept him satisfied on our trip, as we were spooned increasingly thin portions of dal baht.

Day 3: Acclimatisation day in Namche Bazaar, to Hotel Everest View at 3880m

Despite feeling fine and sleeping well enough, we took the recommended acclimatisation day in Namche Bazar, hearing that those who press on are often stricken with sickness further up the hike. The rule ‘hike high, sleep low’ was something of a mantra, so we used our “rest day” to ascend further up the mountain, to a hotel which offered a spectacular view of the summits. Jonny and I are learning Spanish, so when a Spanish man named Viktor caught up with us, we spent the rest of the hike speaking in broken Spanglish. Viktor is fluent in English but he admired our dedication and wanted to help us learn. Although it was good fun to travel with a hiking buddy, I was less enthusiastic about practising my language skills, as by this point I was finding it hard enough to catch my breath without singing verses of “Estralita, donde estas?” Jonny, on the other hand, was in full flow. It was our trip to Everest where he thoroughly surpassed me in Spanish, using his oxygen-rich brain to think up lyrics and challenges in another language while I puffed behind, wondering what day of the week it was.

**Day 4:Namche Bazaar – Tengboche 3860m **(9.2km, 5 hour hike)

On our fourth day we left Namche, hopeful that we had acclimatised and could therefore sleep above 3000m. The Everest trail is not a clear ascent, as you might assume, but incurs many ups and downs, and today was no exception. Everest’s tree-lined path often obscured the fact that we were hiking up a mountain but, through breaks in the forest, we marvelled at the stretching gulf and river far below. This served to remind us how far we had already come, though it paled in comparison to any fleeting glimpses of mountain-tops spied from occasional view-points.

After a fair way up, we saw a small group huddled around a lady who was rasping in short, fast breaths. It was clear she was suffering from altitude sickness, a panic attack or both. This was to be the first helicopter rescue we witnessed on our trip, and certainly not the last. Indeed, although the trail was not highly populated after Namche (sometimes we would only see a handful of other people the whole day), the sound of helicopters chop-chop-chopping through the air was almost as ubiquitous as the clinking of bells as a herd of yaks passed you by on the narrow trail. Many people choose to take a helicopter back down to Lukla from Gorak Shep, near Base Camp, so this will have accounted for some of the rides, but certainly not all.

We continued without incident but I developed a growing breathlessness. I wasn’t worried, only surprised that I felt so unfit after all our work-outs in Bali. Still, the views were stunning and the hike rewarding. We were ravenous by the time we reached Tengboche and allowed Deet to choose our lodge for the sake of brevity. He brought us into the first one we came upon, perched on the top of the gulf and facing the elements. He told us it had the best view of any hotel in the area. Logic should have told us there might be a warmer option further into the town, but we weren’t thinking clearly. Despite only being a few days up the mountain (naturally, it gets colder the higher you get), this was to be one of our coldest nights.

Day 5: Tengboche – Pheriche 4240m (11km, 6 hours)

That night, we got our first true taste of sleeping on the side of the world’s tallest mountain in November. It was freezing. Cardboard-thin walls provided no insulation and – for the sake of a Deet’s beautiful view – we were given a room in which two of the walls were taken up by large windows, providing us with a steady chill. Even with clothes on, cuddled up next to each other to take advantage of body heat, the air itself was so sharp that it was painful to breathe. The next day, we were amused and horrified to find a thick layer of ice had formed on the inside of our windows. So much for a view! By this time I was happy to get hiking quickly so we could thaw in the sun. We enjoyed a quick breakfast (most likely porridge, chips or fried noodles) and head out.

By this time, the cream I had brought along to protect our faces from the harsh elements had crystalised. Nonetheless, we slathered on our ‘pretty’ every day, much to Jonny’s disdain.

There is nothing quite like a crisp, morning hike to shift your sleepiness. The descent from Tengboche was stunning, as a leafless forest hung over our heads, dripping with crystals from the night before. Sun caught the icicles and shimmered, too shaded to provide actual warmth but offering us a spectacle in playful contrast with the gnarled branches. We were certainly pleased to be on the move again. So far as a mountain’s concerned, what goes down must come up, so after our descent through the frozen forest we were unsurprised to see our path begin to wind upwards. The terrain shifts on this day were particularly striking as trees gave way to a vast orange bank, which may have been evocative of warmer climes if it wasn’t for the snow-topped mountains in the near distance.

We had a choice of where to sleep that evening. Pheriche is the slightly closer, lower option and it also contains a clinic to offer emergency care and education on altitude related issues. Before its establishment in 1973, 1-2 trekkers in every 500 would die of altitude sickness in this vicinity. Since, that figure has dropped to 1 in 30,000. Although most travellers stop at Dingboche, we were tired and chose Pheriche. The clinic was closed and the town was dead as we were hiking out of season, but we were too tired to back-track so found a teahouse which was marginally warmer than our previous night’s accommodation, despite being higher up, and enjoyed a tasty dinner alternative to daal baht: chips, baked beans and a fried egg! Determined not to be bested by the cold weather once more, Jonny and I removed the mattress from my single bed and used it as a wall in the creation of an adult fort. We snuggled up in a single bed and wished for sleep.

Day 6: Pheriche – Dingboche 4410m and acclimatisation hike.

Alas, it did not come. Being a little sensitive to fried foods and eggs at the best of times, my tummy protested my choice of dinner. This brought on the effects of altitude sickness and meant I spent the night feeling like I’d run a marathon, despite lying horizontally and unmoving. Breathing in such cold, dry air was painful but, remembering the lady caught between altitude sickness and a panic attack, I made a conscious effort to breathe calmly and deeply. I made up my mind to retrace our footsteps the following morning so as I could acclimatise at lower altitude. Well, that was the plan, at least.

However, ten minutes or so downhill I was feeling remarkably better. Once more, the morning highlighted everything that was exciting about our trip, in contrast to our freezing, often miserable evenings. In that sense as well as the terrain, Everest is a hike of great ups and downs. If this was proper altitude sickness, I told myself, I wouldn’t be feeling any better yet. Most likely, it was just a rough night. Jonny encouraged me to head down if I needed to but, as this day was supposed to be another acclimatisation day anyway, we decided to push on for a short journey to Dingboche and spend the night there. At Dingboche, we completed a short hike so that we would be “hiking high and sleeping low”. Although it was a relatively small achievement, I felt proud to get to the second flag on the hillside, marking an extra 250m above Dingboche.

We stayed put for a while and admired the view, while our bodies magically acclimatised. This was where we learnt Deet’s name was actually Dil. We seemed to be getting on better, so I asked him to show us a photo of his wife and family. He refused, which was a shame, and the atmosphere felt tense again. Nonetheless, we all felt rested from a relatively easy day.

That night, we found a pleasant stable-turned-resthouse, which boasted a wood-fire and the company of a handful of travellers. They suggested we filled our water bottles with hot water and keep them in bed with us. This was a turned out to be a brilliant plan and we enjoyed a relatively cozy night as a result, at least from the neck down! I managed to get a few hours sleep for the first time in three nights and felt remarkably better for it, so we were happy with our decision to press on after all.

Day 7: Dingboche Lobuche 4910m (12km, 6 hours hiking)

That morning, we woke up feeling fresh and eager to continue the hike. We had enjoyed a good night at our lodge and the next hike to Lobuche would put us only 2 days away from our destination. At this point, we were still in two minds as to whether or not we would complete the Chola Pass onto Gokyo Lakes after EBC (adding a few days to our journey) and this certainly felt more doable after some sleep.

Unfortunately, on a morning excursion to the loo I felt a weight lodged somewhere between my chest and my throat. I pulled it up like phlegm (apologies for the graphic description) but the bolus was stubborn and only moved a small amount. I spent five minutes drawing it up and when it finally arrived I was shocked to feel something stiff as a rubber tyre and about the size of a bottle lid dislodge itself into my mouth. Spitting out the morsel, it was a worrying dark red colour, looking and feeling a lot like tissue! Had I coughed up something this horrid the day before, we would have been straight down the mountain, but today we were feeling relatively fired up so it seemed a shame to turn back. I hoped this would be a one-off and decided to forget about it. Certainly, it didn’t seem to bother me again for the rest of the day.

Leaving Dingboche, it wasn’t long before we reached a sharp ascent. At the top lies a Sherpa Memorial site. Prayer flags were spread in abundance over sacred, inscribed stones to memorialise of all the Sherpa who had lost their lives on Everest. Amongst the names were also a few Western ones. Before it got too cold to work our kindles, we had been reading Into Thin Air: an account of one fatal excursion up the mountain, and I recognised a name amongst the stones. So that is how the story ends, we thought, looking across the ghostly site towards our destination which, at a mere 20km away, was nothing compared to what these climbers faced.

When we were to return to this site on the way down, it would be a clear day, offering some of the most stunning views of the trip. However, today was misty and the way hung thick with cloud. It gave the site an eerie atmosphere and the memorial stones jutted upwards from the earth like graves, even as the colourful flags broke up the grey. It is a unique and sacred spot, and we were thankful to catch our breath there before continuing.

As you approach Lobuche, terrain turns to a quarry-like mass of rocks. It is amazing that a settlement, however basic, can have been built here without barely so much as a rough path by which to pass materials. We were tired after our hike and it was windy and cold, but we decided to ascend the edge of town so as to “hike high and sleep low”. Even the mountain goats looked nesh and, as we hid from the sharpest blusters behind a rock at the peak of our ascent, we cuddled to keep warm, catching our breath as we looked down upon Lobuche.

Descending before sunset, we arrived in our teahouse in time to see the mountains lit like flames by the last rays that were touching Earth. Stunning as these were, it offered only a glimmer of the beauty we would see the following day, as we ascended to the highest point of our trek: Kala Patthar.

Day 8: Lobuche – Gorak Shep 5140m and up Kala Patthar 5550m (4.5km hike in 2.5 hours, plus 3.5 hours up and down Kala Patthar)

With another freezing night behind us, I rose to find a similar sensation of heaviness in my chest. Repeating yesterday’s furball-like expulsion, I managed to dislodge a large piece of rubbery, dark red matter. This was starting to get worrying. I showed Jonny, who looked alarmed and reiterated that I might consider heading down the mountain. This was much larger than yesterday’s bloody offering and just as hard and tissue-like. From this moment forth, we referred to these bodily creations as ‘scobies’. For those who have never seen kombucha tea in its purest form, a scoby (literally Symbiotic Culture Of Bacteria and Yeast) is the growing gloop of “good bacteria” that the unsqueamish health-conscious grow in jars and drink daily to keep a healthy gut. Hannah Shackleton used to keep one and treated the monstrosity like some sort of sacrificial pet, much to flatmate Carly’s horror.

I worried that my scoby was of a more dangerous variety and decided to take my emergency antibiotics, in the vague hope that they would ward off anything too nasty. After all, I wasn’t about to descend the mountain now, as Kala Patthar promised to be the highlight of our trip!

[To this day, I have no idea what it was I was pulling from my body, as I have researched and found no mention of anyone dislodging a piece of lung or blood clot through altitude sickness and breathing in sharp, cold air. The closest suggestion I have found is that blood vessels were bursting in my nose, causing blood to mix with mucus, tastelessly slipping down my pharynx and drying somewhere in my oesophagus. Charming.]

You’ll be pleased to hear I shan’t be describing any more clots as that was the largest scoby of the trip. For two days after this, my morning scobies got smaller and smaller, until I was further down the mountain and they disappeared completely. Thank clot for that.

Now, back to the hike.

The way from Lobuche to Gorak Shep was notable for the vast stretches of rocky terrain, which would appear as endless dunes if it were not for the superbowl of white mountains around us, known – I think – as a cirque. It was beautiful in the way an abandoned cathedral might also be: the sky a stained-glass blue, magnificent walls drawing your eyes upwards from grey rubble. However, without rivers or trees to break up the hike it did not have the same dynamic shifts in landscape as other days.

Gorak Shep is famed for being the least developed, coldest settlement, being the highest place a tourist can stay without paying the $40K fee to trek beyond base camp. Therefore, we were pleasantly surprised to find one hotel which claimed to be selling rooms with electric blankets. After yet another night of zero sleep, I requested we spend the extra buck for this luxury. Jonny, who had managed to escape any signs of altitude sickness thus far, was feeling headachey and was happy to concur. Dil seemed displeased. I think he had another frozen tea-room in mind for us where he could get an extra helping of bread in exchange for our frostbitten fingers and toes, but we weren’t budging. We stayed long enough to rest up and eat some dal baht before the sunset hike up Kala Patthar. I was finding it hard to eat anything at all by this point owing to the altitude but I knew it was important to get my energy up for what was bound to be the hardest stint of the hike.

I can’t remember the exact time we set off to hike up Kala Patthar, but unless you’re fit as a fiddle and not feeling the effects of altitude, I’d recommend giving yourself at least an extra half hour to reach the summit, on top of the recommended 2. Of course, you want to time it well because you’re there to see the sun setting on the peak of Everest, so too early and you’ll get cold waiting, too late and you might miss the spectacle!

The sublime views, shortness of breath and ever-elusive summit, imprint on my memory the qualities of a dream. Kala Patthar was a relatively sharp ascent consider-ing the altitude we were at and I took it slowly. However, we were against the clock and did not want to miss sunset, both for the views and the small matter of our de-scent, which we didn’t fancy doing in the dark. At least 3 times, we approached what appeared to be the top of the mountain only for another stretch to rise above us from a deceptive angle. It was only upon seeing a flag upon the steepest and rockiest sum-mit that we knew this must be it. It was little more than a bouldering challenge at the beach but by this point my lungs were screaming. The scramble took ages but we were delighted to reach the top in perfect time. Promising ourselves not to turn around dur-ing the ascent, we did so now to behold Mount Everest and her possy, Lhotse and Nuptse (literally: the Everest Massif) light up the sky as though the crown of the world was on fire.

Most hikers had come and gone by the time we decided to turn back. One or two had misjudged the hike and were still making their way up as the sun’s last rays hit earth. We knew we had left it too late to get all the way down in daylight, but it was worth it. Or, at least it would be worth it if we got down in one piece. Once the summit boulders were behind us, the way would be safe but it was quite a long descent. We had brought head-torches “on the off-chance” we would need them and, were it not for those, we would have been in a sorry state! When the sun is out, trekking is not too cold. Sometimes, Jonny and I would even strip down to long sleeved T-shirts, but a cloudless sky made for pretty extreme cold. Luckily for us, it also meant that the stars were out in full force, so we stopped a couple of times during our descent to lie on the floor and gaze upwards. Two spectacles of vast beauty in under an hour and for once my chest felt heavy with gratitude, rather than lack of oxygen. Stars heaved and settled: celestial fallout from mountains which oxidise in the sunset, shocking the world to stillness. After a few minutes, our cold bodies dragged us back into time and space, and we begrudgingly switched our head torches back on. Needless to say - going at that rate - we were the last ones down.

Day 9: Gorakshep to Everest Base Camp 5364m and back down to Pheriche (3.5km in 2.5hours + 21.5km in 10 hours)

Today was the day. We woke up early in our sub-zero rooms, heaved ourselves out of beds barely warmed by thermal blankets, expelled a modest scoby and set off nice and early, so as to reach EBC and get back to Pheriche in time for the evening. After all, no one wants to spend more than a night in Gorak Shep.

Although the Kala Patthar hike was physically the most challenging, this day took the mental biscuit for me. There was something quite final about reaching the summit of yesterday’s mountain. Whether it was the glorious sunset or the fact that it was in fact higher than EBC, it seemed as though today’s hike was gratuitous by comparison and I nearly decided to give it a miss. After all, I like to think I’m not someone who would do something for the sake of “saying I’d done it” and I didn’t think EBC would have all that much to offer, out of season when we wouldn’t be seeing mountaineers setting off to reach the peak of the world.

Nonetheless, it seemed a shame not to try. In all honesty, I can’t remember much of the scenery on this hike beyond the endless rubble. Up until this point, the nights had been awful but the days had pulled me through, but this time I had real problems motivating myself to walk another step. At one point, I sat down on a rock and had a little cry. We weren’t far from base camp at all, but I didn’t want to move another metre. That’s when a little miracle happened.

A Himalayan Mountain dog came and sat by my side. She was a wild, beautiful fluffy thing with a wet tongue and she licked my tear-stricken face. It was like she had sensed that I needed her help and she didn’t budge until I stood up again. Then, she trotted forwards 50m and waited for me to catch up, before continuing on again and waiting, all the way to base camp. When we arrived, I gave her a huge hug. We had seen dogs, sometimes in small packs, the further up the mountain we climbed, but for this one to arrive at such a pivotal moment and coax me to the finish line was nothing short of a blessing, and I’m not normally one to talk about such things.

Relieved, I sat at the furthest point we were allowed to venture while Jonny and our canine companion stepped under the flags and descended to icy ground where, in April, hikers would begin their ascent. Huge respect for those men and women. Getting to Base Camp alone was more than enough for me!

On our way back, after I’d given a couple of biscuits to my new friend and patted her head as a fond farewell, we stopped by our tea house to collect a few items we had left behind. After all, there was little point carrying heavy bags to Base Camp. When we were there, we chatted to a couple of guys we had met the day before. Last night, there had been three of them, but they said that an air ambulance was on its way to collect their friend who was experiencing altitude sickness and needed to be taken to lower ground. After wishing them luck, we continued down to Pheriche but one of the boys caught up with us and asked to join our pack. After all, his sick friend needed a chaperone in the helicopter, leaving him to trek down alone. We welcomed him and enjoyed trekking down the mountain for the final 2.5 days: one night in Pheriche, one in Namche and finally one in Lukla before our flight back to Kathmandu.

Pheriche - Namche Bazaar and Namche Bazaar - Lukla

These final days we trekked well into darkness but with every step it felt easier to breathe and so I enjoyed our long hikes and appreciated some of the views I had missed from having my face to the ground, counting footsteps on the way up. The Sherpa Memorial site was particularly beautiful as, instead of being spookily shrouded in mist, the clouds opened up to reveal spectacular views of the mountains beyond.

In Namche, Jonny and I paid extra for a hotel with a shower. The last time we had taken our clothes off, let alone washed, was a week ago. Call us disgusting if you must, but there were no showers further up the mountain and the water turned to ice within minutes, so there was little choice in the matter. Besides, whether we had got used to each other’s stench or the cold simply did not allow bacteria to grow, we did not find each other smelly in the slightest. Upon peeling clothes off, I was unsurprised to find I looked a scrawny mess in the mirror, having not eaten or slept properly in a week while we were expending a lot of energy. Removing my socks also revealed bloody feet from where my nails had grown and acted as little saws to neighbouring toes. What I was more surprised to find, however, was a scabby ring around each ankle where my boots had rubbed, unbeknownst to me, leaving me looking like I’d trekked the mountain in shackles. I have no idea how this hadn’t caused me any discomfort and I only hoped they would clear up before the wedding.

Overall, we were not looking our best and we decided to treat ourselves to a nice hotel upon arrival back in Kathmandu. We’re talking hot showers and room service and absolutely no reason to leave for at least three days. The thought of it almost brought tears to our eyes.

Our final day of hiking was yet another long one, finishing in darkness. It also meant saying goodbye to Dil, which I believe we were mutually looking forward to. Over the last couple of days, he had been less stand-offish, even choosing to show me a photo of his wife, which previously he had hidden from us. This may have been to secure a tip but perhaps he was simply in a good mood, knowing that home was not far away. For all his grumbling, it had been very useful having him to carry some of our gear, so we were appreciative. That being said, we didn’t end up using lots of it, including my laptop, though at least all the marshmallows had been eaten. When it came to our farewell, we gave Dil the agreed amount, plus an extra day’s pay as a tip, which we heard was customary. We also bestowed on him some trekking gear, like poles and leggings, which we did not think we would need when leaving the mountain. However, Dil did not seem pleased:

Me: Here Dil, your pay and here is pay for an extra day. Thank you very much.

Dil: No tip?

Me: Yes. Extra day is tip.

Dil: Eye roll.

Needless to say, we were looking forward to our own company for a while.

The next morning, our plane was delayed but we got going eventually. Back in Nepal, a cow mounted our taxi and gave the windshield a lucky lick. It’s a good thing they’re sacred to Hindus or I think the cab driver would have thrown a wobbly. We got dropped off at our hotel, where they had fluffy toys in abundance and a Christmas grotto themed restaurant. Tacky but brilliant.

Unfortunately, the water was piss-yellow, making bathing slightly less appealing, but we weren’t put off. We were pleased to share a dinner with fellow hiker, Viktor, who had completed a different and much more impressive trek than us and arrived back at the same time. We put our feet up, ate good food and relaxed. After three days of TLC, we were ready for our next adventure in Chitwan National Park to find wild rhinos. Little did we know it would land both of us with typhus!

I feel like I should finish this mammoth write-up with some pearls of wisdom but I’m not sure I have many to offer. If you’re trekking to Base Camp, I recommend doing it in season, around April. Don’t bring laptops and try to get your weight down so you can carry your own gear; it isn’t like you’ll be changing clothes much anyway. Bring bottles you can fill with hot water for night times and make sure you pack an abundance of sucky sweets. Trek Kala Patthar at sunset, not sunrise. Perhaps go the Gokyo Lakes route on your way up, in case – like us – you don’t have the energy to do it on the way back. Bring crampons if you’re planning to walk one of the icy passes (we got some from fellow hikers who had no further need of them but decided against going when we heard that 3 people had died on the passes that week). Learn to love dal baht. Take your time: spend an extra day acclimatising and do a side-hike to make sure you’re trekking high, sleeping low. Treat yourself to a break afterwards. Take the gloves off for photos now and again (yes, I know it’s freezing) because despite being tough, it is a truly stunning hike.

- Completed Challenges

- Upcoming Challenges

- Send us a Challenge